Stander

© Bella Stander

.

book reviews

Grange House

by Sarah Blake

(Picador)San Francisco Chronicle

July 30, 2000

by Bella StanderSarah Blake has a doctorate in Victorian literature, and it shows. In Grange House, her first novel, she has constructed a nearly seamless pastiche of favorite 19th century literary genres (ghost story, romance, Gothic horror, mystery) and themes (doomed love, secret birth, abandoned children, sudden death, madness, mistaken identity).

The first 40 pages alone have overt references to Swinburne, Wordsworth, The Mill on the Floss, Jane Eyre, Sir Walter Scott and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, with countless thematic links throughout the book to, most notably, Edith Wharton and Henry James, as well as Poe and any number of lesser lights. In fact, Grange House is ripe for the plucking as a "spot the allusion" assignment for some English lit student and should inspire much discussion in book groups as well.

But even someone ignorant of the literary shoulders Blake is standing on should enjoy Grange House, for above all it's an enchanting tale by a consummate storyteller. Besides her academic expertise, what also shows is Blake's poetic mastery of language and love for the austere beauties of coastal Maine, where the novel (with brief diversions to a Brooklyn mansion) is set.

Consider these descriptions of the view from the eponymous waterside hotel for the wealthy in the summer of 1896, offered by one of the "rusticators" (city dwellers), 17-year-old narrator Maisie Thomas:

"Behind the covering of gauzy white curtains hung a dense fog, from which the dark shapes of trees poked like bony fingers out of tattered gloves. . . . The fog blew between the dark trunks, leaving soft clumps upon the low branches like old women's hair . . ." And that evening: "I turned away to look out upon the twilight, the sharp tops of the trees cutting a ragged black line along the sky streaked with clouds and the leftover color of the day."

In between, Maisie witnesses the recovery of the drowned bodies of childhood companion Halcy, the cook's daughter, and Henry, Halcy's fiance, found clinging to each other and a boat's broken mast. Just after that first glimpse of morning fog, Maisie had seen a ghostly figure waving farewell; only later does she realize it was Halcy.

One of the men who recovers the dead is Bart Hunnowell, a 30-year-old bon vivant travel writer, who competes for Maisie's affections with staid Jonathan Lanman, a junior partner in her father's New York business. Though Jonathan initially takes the lead, anyone who's read a 19th century novel (or a 20th century romance) knows who will ultimately win Maisie's heart, for the clues are obvious: Bart's last name evokes bounty and sweetness while his rival's twists the tongue; Maisie is flustered by Bart and deems him ``perplexing''; and most telling of all, after Jonathan "dismissively" quotes a Rossetti poem describing his mistress, Bart declares, "When my beloved is incomprehensible, she is endless. And I would follow her into that blank unknown." What young woman reared on Schiller and Wordsworth, Bronte and Eliot, wouldn't prefer such a man?

First, though, Maisie has to follow her own path into the blank unknown. And the person who leads the way is former author Miss Grange, the mysterious "possessing spirit of the place," who lives in the attic of the house built by her vanished ancestors. The older woman brings Maisie to a clearing in the woods behind the house, where Maisie has another unearthly vision, confirming that she possesses "the capacity to see . . . (t)o imagine . . . and so to recognize the hidden story, the hidden life that speaks in charms and whispers and will not show its face, save halfly."

In other words, Maisie is a budding writer (though she doesn't know it yet). And perhaps to help her recognize that hidden story -- or is there another reason? -- Miss Grange tells a tale of how the house was haunted by the ghost of the baby her mother left behind in Ireland.

Subsequently, she shows Maisie a little grave in the woods and charges her to finish the "unwritten story" that led to Halcy's death. She explains to the bewildered girl, "Some stories are only fathomed in the writing of them."

As is to be expected in a novel that begins with a ghost and a double death, tragedy strikes hard and increasingly often as Maisie's story and the contrapuntal one related by Miss Grange unfold and eventually intertwine. In her one misstep, Blake rudely breaks the dreamlike flow of the narrative at the end of Volume I by using what Vladimir Nabokov described as "that dismal feature of 18th century English and French novels, information conveyed by letters."

This reader was so outraged by the creaking authorial machinery that it took quite a few more pages before she was once more lulled into a willing suspension of disbelief. That renewed trust was well rewarded, though, for this is a complex and finely wrought work that on one level satisfies with old-fashioned mystery and romance, and on another disturbs with searching questions about the nature of literature, writers and storytelling.

© 2000 Bella Stander

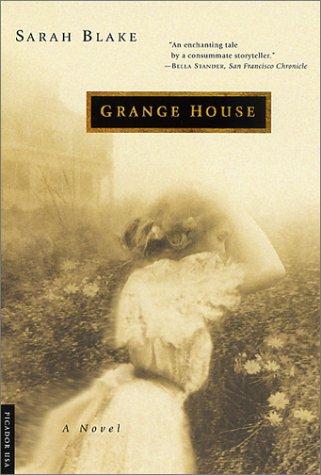

Cover of paperback edition

book reviews interviews articles